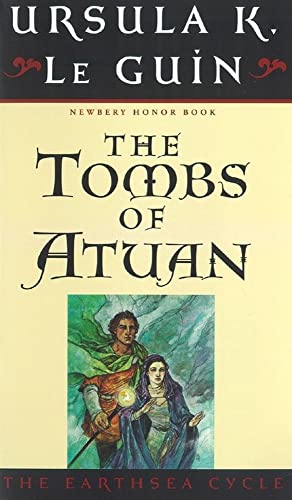

Jonathan Zacsh reviewed The Tombs of Atuan by Ursula K. Le Guin (Earthsea Cycle, #2)

a bit slow feeling til the end

3 stars

2nd read: beautiful ending

Mass Market Paperback, 180 pages

English language

Published Sept. 1, 2001 by Aladdin Paperbacks.

The Tombs of Atuan is a fantasy novel by the American author Ursula K. Le Guin, first published in the Winter 1970 issue of Worlds of Fantasy, and published as a book by Atheneum Books in 1971. It is the second book in the Earthsea series after A Wizard of Earthsea (1969). The Tombs of Atuan was a Newbery Honor Book in 1972. Set in the fictional world of Earthsea, The Tombs of Atuan follows the story of Tenar, a young girl born in the Kargish empire, who is taken while still a child to be the high priestess to the "Nameless Ones" at the Tombs of Atuan. Her existence at the Tombs is a lonely one, deepened by the isolation of being the highest ranking priestess. Her world is disrupted by the arrival of Ged, the protagonist of A Wizard of Earthsea, who seeks to steal the half of …

The Tombs of Atuan is a fantasy novel by the American author Ursula K. Le Guin, first published in the Winter 1970 issue of Worlds of Fantasy, and published as a book by Atheneum Books in 1971. It is the second book in the Earthsea series after A Wizard of Earthsea (1969). The Tombs of Atuan was a Newbery Honor Book in 1972. Set in the fictional world of Earthsea, The Tombs of Atuan follows the story of Tenar, a young girl born in the Kargish empire, who is taken while still a child to be the high priestess to the "Nameless Ones" at the Tombs of Atuan. Her existence at the Tombs is a lonely one, deepened by the isolation of being the highest ranking priestess. Her world is disrupted by the arrival of Ged, the protagonist of A Wizard of Earthsea, who seeks to steal the half of a talisman buried in the treasury of the Tombs. Tenar traps him in the labyrinth under the Tombs, but then rebels against her teaching and keeps him alive. Through him she learns more of the outside world, and begins to question her faith in the Nameless Ones and her place at the Tombs. Like A Wizard of Earthsea, The Tombs of Atuan is a bildungsroman that explores Tenar's growth and identity. Tenar's coming-of-age is closely tied to her exploration of faith and her belief in the Nameless Ones. The Tombs of Atuan explores themes of gender and power in the setting of a cult of female priests in service to a patriarchal society, while providing an anthropological view of Kargish culture. Tenar, who became the subject of Le Guin's fourth Earthsea novel, Tehanu, has been described as a more revolutionary protagonist than Ged, or Arren, the protagonist of The Farthest Shore (1972), the third Earthsea volume. Whereas the two men grow into socially approved roles, Tenar rebels and struggles against the confines of her social role. The Tombs of Atuan shares elements of the story of a heroic quest with other Earthsea novels, but subverts some of the tropes common to the genre of fantasy at the time, such as by choosing a female protagonist, and a dark-skinned character.The Tombs of Atuan was well received when it was published, with critics commenting favorably on the character of Tenar, Le Guin's writing, and her "sensitive" portrayal of cultural differences between the Kargish people and the people of the rest of Earthsea. The story received praise for its exploration of religious themes and ethical questions. Le Guin's treatment of gender was criticized by several scholars, who stated that she had created a female protagonist, but within a male-dominated framework. Nonetheless, the novel has been described by scholars and commentators as "beautifully written", and a "significant exploration of womanhood".

2nd read: beautiful ending

Maameren tarinoita en nuorena lukenut, jostain ihan eri yhteydestä bongasin Holvihaudat ja päätin lukea. Oikeana päivänä syntynyt pikkutyttö saa jatkaa papitarten jälleensyntymisen linjaa ja hänet vihitään vartioimaan pimeitä käytäviä ja holveja maan alla. Missä ei ketään saisi olla, löytyy mies, jonka oikeastaan pitäisi menettää henkensä, mutta Tenar säästää hänet.

Pimeiden, kosteiden käytävien tunnelma välittyi hyvin. Perinne painaa, pääseekö siitä irti?

This was technically a reread for me, but the last time I read it, the century had not yet turned—and in any case, I remembered nothing about it, other than something about a cave.

The Tombs of Atuan is quite good, but I see why it is, perhaps, less popular than some of Le Guin’s other works. It’s a sequel to A Wizard of Earthsea, but where Earthsea is practically a fairy tale in tone, stylized and sonorous (which is an endorsement, not a criticism, by the way), Atuan is more directly a “fantasy novel.” It is not, however, a comforting one, not one where all the pieces fall together nicely, everybody’s problem is solved, the main characters fall in love, and so forth.

It is a story of beginnings, I think: first of the protagonist’s life as Arha, and then, the re-beginning—or perhaps better said, the …

This was technically a reread for me, but the last time I read it, the century had not yet turned—and in any case, I remembered nothing about it, other than something about a cave.

The Tombs of Atuan is quite good, but I see why it is, perhaps, less popular than some of Le Guin’s other works. It’s a sequel to A Wizard of Earthsea, but where Earthsea is practically a fairy tale in tone, stylized and sonorous (which is an endorsement, not a criticism, by the way), Atuan is more directly a “fantasy novel.” It is not, however, a comforting one, not one where all the pieces fall together nicely, everybody’s problem is solved, the main characters fall in love, and so forth.

It is a story of beginnings, I think: first of the protagonist’s life as Arha, and then, the re-beginning—or perhaps better said, the resumption of the beginning—of it as Tenar. The quest which is completed, for the Ring of Erreth-Akbe, is Ged’s quest, not Tenar’s; and as such is mentioned only in passing, only enough as needed to satisfy plotting, since this is her story, not Ged’s. She escapes: with his help, she sees through the lies and shackles laid upon her as Arha, and so she sails with Ged to his own lands, where he has promised he will make a place for her, first, temporarily, with the “princes and rich lords” and eventually, more permanently, with his own master and teacher, the wise mage Ogion, none of whom she has ever known. The book ends as they have sailed into the harbor with the Ring, whose magic promises peace and order:

Tenar sat in the stern, erect, in her ragged cloak of black. She looked at the ring about her wrist, then at the crowded, many-colored shore and the palaces and the high towers. She lifted up her right hand, and sunlight flashed on the silver of the ring. A cheer went up, faint and joyous on the wind, over the restless water. Ged brought the boat in. A hundred hands reached to catch the rope he flung up to the mooring. He leapt up onto the pier and turned, holding out his hand to her. ‘Come!’ he said smiling, and she rose, and came. Gravely she walked beside him up the white streets of Havnor, holding his hand, like a child coming home.

She may be like a child coming home, in the sense that, having begun her new reassumed life, she must trust him, and he leads her, but the irony is that however much like that child she may be, she cannot go home, for at this point in the story she has no home. Nor do any of those purportedly “joyous” actually know her; they only see what the ring she wears represents. All that she had is gone, and even Ogion’s wisdom is only a promise for the future. For her, however gravely (and bravely) she faces it, there is no indication here of what happens next—her quest has just begun.

Compare it to the ending of A Wizard of Earthsea, where Ged, having sought and defeated the “shadow” with the help of his friend Estarriol, returns to the latter’s home island, where his sister waits for them.

[T]he voyage to Iffish was not long. They came in to Ismay harbor on a still, dark evening before snow. They tied up the boat Lookfar that had borne them to the coasts of death’s kingdom and back, and went up through the narrow streets to the wizard’s house. Their hearts were very light as they entered into the firelight and warmth under that roof; and Yarrow ran to meet them, crying with joy.

This is the end of the arc, not the beginning. It’s a quieter but more real homecoming, to hearth and family and the promise of belonging. The contrast to the end of Tenar’s story could not be more striking. She has only possibility, and hope.

Besides what I’ve noted above, there is another aspect to the book’s realism, too, which Le Guin herself notes in the afterward in the edition I have.

Some people have read the story as supporting the idea that a woman needs a man in order to do anything at all (some nodded approvingly, others growled and hissed). Certainly Arha/Tenar would better satisfy feminist idealists if she did everything all by herself. But the truth as I saw it, and as I established it in the novel, was that she couldn't. My imagination wouldn't provide a scenario where she could, because my heart told me incontrovertibly that neither gender could go far without the other. So, in my story, neither the woman nor the man can get free without the other…. Each has to ask for the other's help and learn to trust and depend on the other. A large lesson, a new knowledge for both these strong, willful, lonely souls.

Not really in line with the sort of individualistic ethos which held sway when Le Guin was writing, and still holds most of society in its grip today.

All of which is a long-winded way of saying, my point is that The Tombs of Atuan disappoints, potentially, both those who loved A Wizard of Earthsea and wanted more, not something different, as well as those—though surely the groups aren’t mutually exclusive—who want escapism, not realism, out of their fantasy. (Not that Earthsea is escapist in that sense either.) But even if those describe you, I still think you should read Atuan. Just know what you’re getting into.

Content warning Literally quotes the ending (and of A Wizard of Earthsea)

This was technically a reread for me, but the last time I read it, the century had not yet turned—and in any case, I remembered nothing about it, other than something about a cave or tunnels.

The Tombs of Atuan is quite good, but I see why it is, perhaps, less popular than some of Le Guin’s other works. It’s a sequel to A Wizard of Earthsea, but where Earthsea is practically a fairy tale in tone, stylized and sonorous (which is an endorsement, not a criticism, by the way), Atuan is more directly a “fantasy novel.” It is not, however, a comforting one, not one where all the pieces fall together nicely, everybody’s problem is solved, the main characters fall in love, and so forth.

It is a story of beginnings, I think: first of the protagonist’s life as Arha, and then, the re-beginning—or perhaps better said, the resumption of the beginning—of it as Tenar. The quest which is completed, for the Ring of Erreth-Akbe, is Ged’s quest, not Tenar’s; and as such is mentioned only in passing, only enough as needed to satisfy plotting, since this is her story, not Ged’s. She escapes: with his help, she sees through the lies and shackles laid upon her as Arha, and so she sails with Ged to his own lands, where he has promised he will make a place for her, first, temporarily, with the “princes and rich lords” and eventually, more permanently, with his own master and teacher, the wise mage Ogion, none of whom she has ever known. The book ends as they have sailed into the harbor with the Ring, whose magic promises peace and order:

Tenar sat in the stern, erect, in her ragged cloak of black. She looked at the ring about her wrist, then at the crowded, many-colored shore and the palaces and the high towers. She lifted up her right hand, and sunlight flashed on the silver of the ring. A cheer went up, faint and joyous on the wind, over the restless water. Ged brought the boat in. A hundred hands reached to catch the rope he flung up to the mooring. He leapt up onto the pier and turned, holding out his hand to her. ‘Come!’ he said smiling, and she rose, and came. Gravely she walked beside him up the white streets of Havnor, holding his hand, like a child coming home.

She may be like a child coming home, in the sense that, having begun her new reassumed life, she must trust him, and he leads her, but the irony is that however much like that child she may be, she cannot go home, for at this point in the story she has no home. Nor do any of those purportedly “joyous” actually know her; they only see what the ring she wears represents. All that she had is gone, and even Ogion’s wisdom is only a promise for the future. For her, however gravely (and bravely) she faces it, there is no indication here of what happens next—her quest has just begun.

Compare it to the ending of A Wizard of Earthsea, where Ged, having sought and defeated the “shadow” with the help of his friend Estarriol, returns to the latter’s home island, where his sister waits for them.

[T]he voyage to Iffish was not long. They came in to Ismay harbor on a still, dark evening before snow. They tied up the boat Lookfar that had borne them to the coasts of death’s kingdom and back, and went up through the narrow streets to the wizard’s house. Their hearts were very light as they entered into the firelight and warmth under that roof; and Yarrow ran to meet them, crying with joy.

This is the end of the arc, not the beginning. It’s a quieter but more real homecoming, to hearth and family and the promise of belonging. The contrast to the end of Tenar’s story could not be more striking. She has only possibility, and hope.

Besides what I’ve noted above, there is another aspect to the book’s realism, too, which Le Guin herself notes in the afterward in the edition I have.

Some people have read the story as supporting the idea that a woman needs a man in order to do anything at all (some nodded approvingly, others growled and hissed). Certainly Arha/Tenar would better satisfy feminist idealists if she did everything all by herself. But the truth as I saw it, and as I established it in the novel, was that she couldn't. My imagination wouldn't provide a scenario where she could, because my heart told me incontrovertibly that neither gender could go far without the other. So, in my story, neither the woman nor the man can get free without the other…. Each has to ask for the other's help and learn to trust and depend on the other. A large lesson, a new knowledge for both these strong, willful, lonely souls.

Not really in line with the sort of individualistic ethos which held sway when Le Guin was writing, and still holds most of society in its grip today.

All of which is a long-winded way of saying, my point is that The Tombs of Atuan disappoints, potentially, both those who loved A Wizard of Earthsea and wanted more, not something different, as well as those—though surely the groups aren’t mutually exclusive—who want escapism, not realism, out of their fantasy. (Not that Earthsea is escapist in that sense either.) But even if those describe you, I still think you should read Atuan. Just know what you’re getting into.

It's the kind of story I'd like to follow a bit further. Also, I'd love some more exploration of how the reality and the worship are connected. But I was happy as it was.

It's the kind of story I'd like to follow a bit further. Also, I'd love some more exploration of how the reality and the worship are connected. But I was happy as it was.

As with Book 1, this suffers from audiobook narration that is not terribly engaging by today's standards.

That said, it takes a really long time to figure out how in the heck this is part of Ged's story. And, understanding some time has passed since we saw him last, he doesn't at all feel like the same person. It would have almost felt more satisfying to me as something that happens in Earthsea, sure, but wasn't part of Ged's tale, because it feels so disconnected.

As with Book 1, this suffers from audiobook narration that is not terribly engaging by today's standards.

That said, it takes a really long time to figure out how in the heck this is part of Ged's story. And, understanding some time has passed since we saw him last, he doesn't at all feel like the same person. It would have almost felt more satisfying to me as something that happens in Earthsea, sure, but wasn't part of Ged's tale, because it feels so disconnected.

The Tombs of Atuan is Book #2 in The Tales of Earthsea, a high fantasy series by Ursula K. Le Guin. Tombs is about a young girl named Tenar, who is taken from her home to become a priestess in the middle of a desert, where nothing ever seems to change, and the world outside is something evil, and to be feared.

I would have at first complained that the first 40% or so of The Tombs of Atuan is quite slow. And it’s true, I struggled to push forward. Comparing it to Ged’s adventure in The Wizard of Earthsea, to see a young girl taken from her home and turned into the head priestess/human goddess of darkness, things were bleak, and slow, and dull. But that was the point.

As I got to the middle, I ate the rest of the book up with vigor. I love Tenar. She …

The Tombs of Atuan is Book #2 in The Tales of Earthsea, a high fantasy series by Ursula K. Le Guin. Tombs is about a young girl named Tenar, who is taken from her home to become a priestess in the middle of a desert, where nothing ever seems to change, and the world outside is something evil, and to be feared.

I would have at first complained that the first 40% or so of The Tombs of Atuan is quite slow. And it’s true, I struggled to push forward. Comparing it to Ged’s adventure in The Wizard of Earthsea, to see a young girl taken from her home and turned into the head priestess/human goddess of darkness, things were bleak, and slow, and dull. But that was the point.

As I got to the middle, I ate the rest of the book up with vigor. I love Tenar. She embodies so much of what it is to be a person struggling with a broken identity and a sense of loss. And yet she has such strength. As Ged tells her: she is a light in the darkness. And Ged, too, I adore. He is so calm and powerful, and all he asks is that Tenar trusts him. When she finally sees his strength, when her old life crumbles before her very eyes, it was truly an emotional experience. “Trust me.” What weight those words carry.

I love the darkness in the series thus far. Not only is it a physical entity, but it is also the darkness within us. Hopelessness, depression, the loss of faith. Oppression. Whether an outside force or otherwise, it is all connected. It is truly beautiful and terrifying.

In Le Guin’s Afterward, she says that feminists might argue that Tenar is shown to be another heroine in need of a man to save her. But she explains this is not so, and I agree completely: One could not have saved themself without the other. Tenar, the only one with the knowledge of the tombs, needed to see the outside world in the form of Ged in order to even think of saving herself. And Ged, with the power to fight off the darkness (and only for a time), could not have escaped without her knowledge and care for saving his life. I doubt that he would have ever left without her after meeting her. Not because it was he who had to save her, but that her world was so cruel that he could not live with himself to have done otherwise.

The second to last chapter, I got really emotional when Ged told Tenar that he could not stay with her. She asks, unable to meet his eyes, and he says no. He would cross the ends of the earth for her, but he could not stay. He has callings elsewhere. It is. Sad as f*ck. Le Guin doesn’t explain it, doesn’t go into detail, merely shows Ged looking off into the distance, and Tenar going inward, going silent.

I cried for several pages of the next chapter, just because of that one scene. It was as if they had already said goodbye, like they were already parting ways, even though it was not the end. I hate goodbyes. She had learned to trust this man, the only person away from the only life she had ever known, and now it felt as though he was abandoning her. (He was not, but to a child and even to my child’s heart, it felt like it.) They finally reach Ged’s boat and he can tell that she is pained, but they both go silent, and Ged goes into a trance. The darkness tries to swallow her: it is still here, still so far away from the broken, crumbled Tombs of Atuan, inching ever closer, to commit one final act of evil: to kill Ged, because after all, he tricked her. Forced her to leave the only life she knew, only to abandon her. She hides the knife behind her back, and Ged opens his eyes, sees her, and we all know that he knows the knife is there. But he gets up, seemingly energized, and speaks. And his voice melts the darkness away. Despite the pain. Despite that feeling of betrayal. She loves Ged. She is sad, but she loves Ged.

Goodbyes are so, so hard. Even if they aren’t forever, they can feel as if they are so. I am glad, at least, that their temporary goodbye is not how the book ends.

The Tombs of Atuan reads simple at times, but it leaves plenty of room for the imagination. Even a simple phrase, “I cannot stay with you”, was enough to bring me to tears. Oh, Tenar, you poor girl. Maybe I’m just a sucker for sentimentality, but the second half made up for any misgivings I may have originally given the first.

This engaging story follows Arha, a child who is tragically taken from her loving mother to act as a high priestess in what was essentially a religous cult. She is separated from everyone else from an early age, and forced to lead a very narrow life that she has been indoctrinated to value. Then, just as she is coming of age, an intruder enters her domain. Fortunately, she is still young and curious (and, perhaps, lonely) enough to question him--and keep him alive instead of having him killed, as she is expected to do.

During this enlightenment, this intruder reminds Arha of her real name (her birth name), and explains his mission, helping her to see her life and surroundings more objectively. In the end, she makes her own decision. I don't think it's spoiling anything to say that this former priestess does escape her old life, but I'll leave …

This engaging story follows Arha, a child who is tragically taken from her loving mother to act as a high priestess in what was essentially a religous cult. She is separated from everyone else from an early age, and forced to lead a very narrow life that she has been indoctrinated to value. Then, just as she is coming of age, an intruder enters her domain. Fortunately, she is still young and curious (and, perhaps, lonely) enough to question him--and keep him alive instead of having him killed, as she is expected to do.

During this enlightenment, this intruder reminds Arha of her real name (her birth name), and explains his mission, helping her to see her life and surroundings more objectively. In the end, she makes her own decision. I don't think it's spoiling anything to say that this former priestess does escape her old life, but I'll leave it at that. And yes, we do meet the main character from the first book (somewhat older and definitely wiser).

The Tombs of Atuan is written in a pleasing style that is paced well with a nice amount of description and detail. I have a high tolerance for detail in realistic novels, but the same amount of detail in science fiction and fantasy is sometimes hard for me to follow. This is no doubt due to a lack of imagination on my part--but anyway, this novel was quite enjoyable, and I look forward to reading the next book of this series.